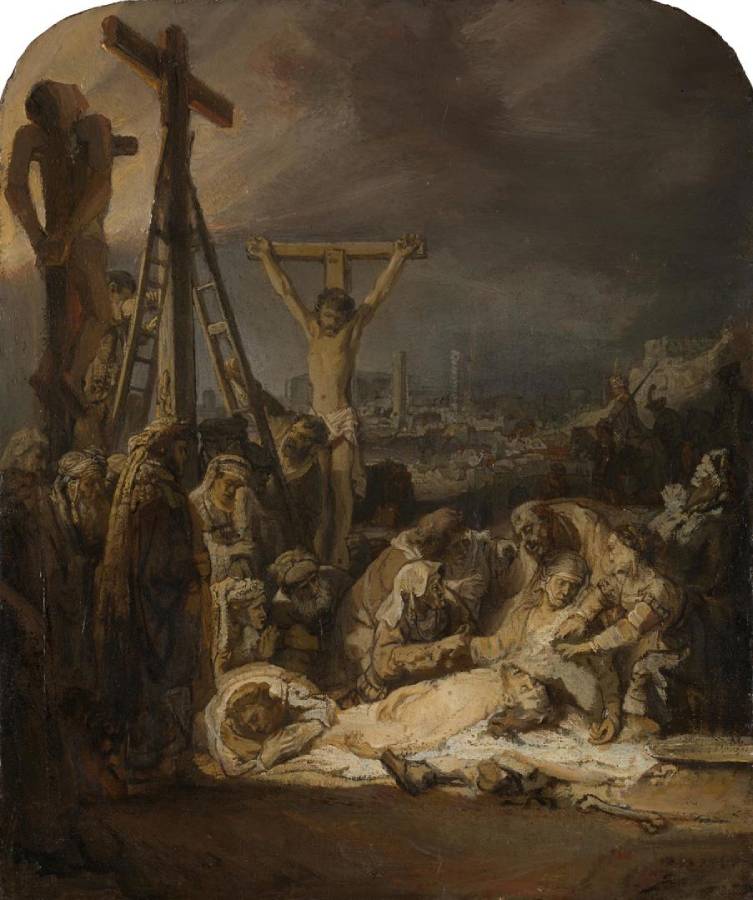

Rembrandt (1606-1669)

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ

c.1635

Oil on paper and pieces of canvas, mounted onto oak, 31.9 x 26.7 cm

National Gallery, London

Christ’s body has just been taken down from the Cross, and his family and followers mourn over him – a moment known as the Lamentation. The central group here are defined by their expressions of intense grief. A variety of onlookers surround them, and the scene extends into a receding cityscape that gives this small picture a grandiose air.

Rembrandt has cleverly used the lighter end of his tonal range so that the Virgin Mary and Christ’s body are illuminated, standing out in this dark picture. Mary has fainted, and almost looks like an extension of her son; a woman dressed in a white headscarf holds her limp right hand. The older man supporting her reclining body has been identified as Nicodemus. Meanwhile, Mary Magdalene passionately embraces Christ’s feet.

This work is accepted as an autograph grisaille (a picture painted in shades of black, white and grey) by Rembrandt. The top and bottom bits, however, are later additions by a different hand, although probably made under Rembrandt’s supervision. The picture has a very complex makeup. Rembrandt himself began by making an oil sketch on paper; he then tore out a section and mounted the rest on canvas. He continued the design on the canvas at the lower right. Finally, someone added canvas strips at the top and bottom, completing what we see today.

The picture is likely a study for an etching that was never executed, and there is some iconographical evidence to support this claim. Christ was crucified alongside two men, the so-called Good Thief and Bad Thief. In this picture, the Bad Thief – identifiable by his twisted body hanging in darkness – would have been on Christ’s right-hand side, which was traditionally reserved for the Good Thief. However, when making an etching the whole composition is reversed in the printmaking process; the positions of the two thieves would have therefore been reversed. Rembrandt’s Ecce Homo, another grisaille in the National Gallery’s collection, was made as a preparatory study for an etching that we know still exists in two different states.

Rembrandt made a drawing of the same subject while he was working on this grisaille, which is now in the British Museum, London – it is a study related to the lower part of the picture. Similarly to the painting, Rembrandt made many alterations and additions to his drawing. The laborious processes of these Lamentations must have meant that Rembrandt was invested in the subject. (NG)