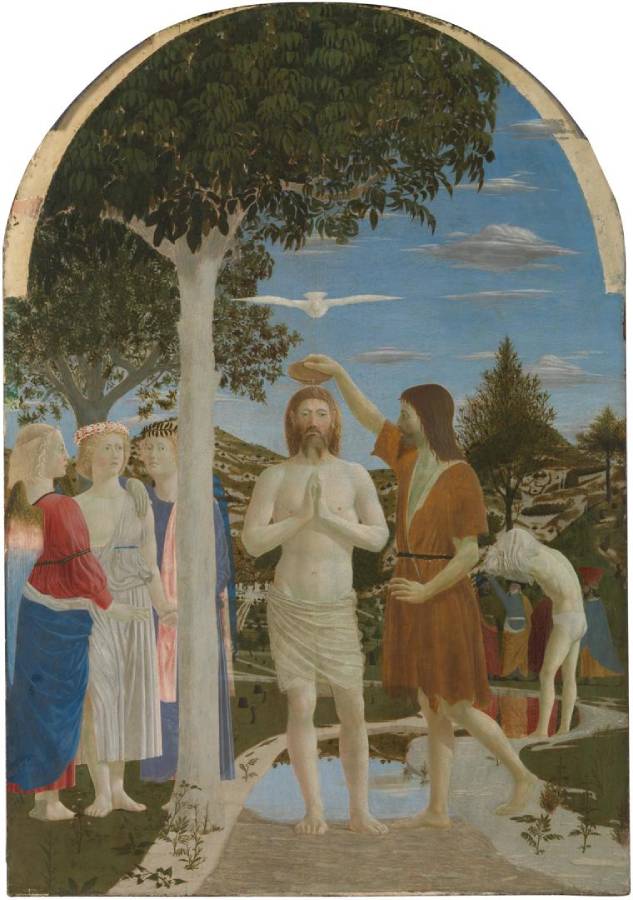

Piero della Francesca (c.1416-1492)

Battesimo di Cristo (The Baptism of Christ)

probably about 1437–1445

Egg tempera on poplar, 167 × 116 cm

National Gallery, London

This is the earliest surviving work by the innovative Tuscan painter, Piero della Francesca. Very few of his works survive, but there are three in our collection. Here, Piero used mathematical principles to order his simple design, creating a visually harmonious image, and set it within a landscape familiar to its original viewers, uniting them personally with this moment in the history of Christianity.

Christ stands in a shallow, winding stream as Saint John the Baptist reaches up to pour a small bowl of water over his head. We can see the water trickling over Christ’s hair onto his forehead. Three angels, with colourful robes and multicoloured wings, witness the event; two of them hold hands while one leans amiably on his companion’s shoulder.

John had been preaching in the wilderness, encouraging people to repent of their sins and to be baptised: the river’s water symbolised the washing away of sin. In the background a man bends over as he takes off his tunic in preparation for his turn. When Christ came to John asking to be baptised, the latter initially refused: as the Son of God, Christ was already sinless. Christ’s insistence was an expression of his humanity and humility. It was at this moment, though, that his divinity was announced. According to the Gospels, the voice of God declared, ‘This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased’ (Matthew 3: 16) and the Holy Ghost descended upon Christ in the form of a dove. Piero has shown the dove as though flying out of the picture towards us. The angel wearing a garland of roses gasps – the only sign of commotion in the picture.

Christ’s baptism, as recorded in the Gospels, was likely to have involved full immersion in the river Jordan, but it was more usually depicted like this. The mirror-like surface of the water in the distance reflects the wooded mountains, the glassy effect contrasting with the otherwise chalky look of the egg tempera paint Piero used. Curiously, the water seems to stop flowing at Christ’s feet – we see the pebbles of the riverbed in the foreground of the picture instead. Piero may have been inviting us to imagine we are standing in the river, looking straight through the clear water.

Piero made this picture for the Camaldolese Abbey of his hometown of Borgo Sansepolcro – the walls and turrets in the distance are probably supposed to represent the town. The valley setting resembles the landscape around the town encouraging worshippers to imagine the extraordinary moment occurring on their doorstep. The mountains in the distance, the stream and the walnut tree were features of the local landscape. According to legend, the town had links with Christ’s homeland from its origin in the eleventh century. A miracle occurred when two pilgrims travelling back from the Holy Land decided to rest beneath a walnut tree: when they woke up, their knapsack containing holy relics had flown up to one of the tree’s highest branches. This miraculous event led to the town’s foundation, which was named after the pilgrims’ relic of a stone from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Piero included a variety of species of plants which are still native to the area today, and which would have been instantly recognisable to the painting’s very first viewers.

What should we make of the tiny figures – singled out by their large, unusually shaped hats – just beyond the bend in the river? They might be intended to represent the three wise men from ‘the East’ who, guided by a star, visited the newborn Christ to offer him gifts. The feast of the Epiphany, which celebrated the event, was held on 6 January, the same day that Christ’s baptism was celebrated. The people of Sansepolcro would have recognised these headdresses as Byzantine: in the same decade as this picture was made, Greeks from Constantinople, the capital of Byzantium, came to Italy to attend the councils which attempted to unite the eastern Orthodox and western Catholic Church. Artists took the opportunity to sketch the foreign visitors, and they began to find their way into Italian paintings as symbols of the East.

As well as rooting the scene in the local area, Piero also uses mathematics to make it look convincingly three-dimensional. Piero – whose father had hoped he would become a merchant, like him – was thoroughly trained in mathematics. He was the first artist to write a treaty on perspective, De prospectiva pingendi, using mathematics to explain how to paint objects in proportion so that they appear in the painting as they are seen in real life. Here he used a grid structure as a guide for the placement and scale of objects. The layering of the elements of this picture – the angels occupy a space between two trees, and the man removing his gown is set between the distant figures in their elaborate headdresses and John the Baptist – echoes this invisible grid. The figures, carefully placed behind one another and gradually getting smaller, lead us into the painting, as does the river that winds away from us. In this way, Piero emphasised the depth of the landscape and the harmony of the figures and natural features within it.

The visual harmony which comes from the figures and features seeming to inhabit the landscape so naturally is one reason that the picture seems to instil a sense of calm. Piero gave the figures, particularly Christ and John, graceful poses: both appear mindful of their bodies and actions, encouraging us too to find stillness in our contemplation. He has directed our gaze to Christ’s body, the anchor of the scene, reinforcing this through the strict alignment of the dove, the bowl and Christ’s praying hands. This vertical line is doubly strengthened by the pale trunk of the walnut tree, which matches Christ’s white flesh.

At some point in the 1460s the panel was joined by two side panels, pilasters and a predella with gilded backgrounds, painted by Matteo di Giovanni, another local artist. (NG)

See also:

• Sansepolcro (Italia)