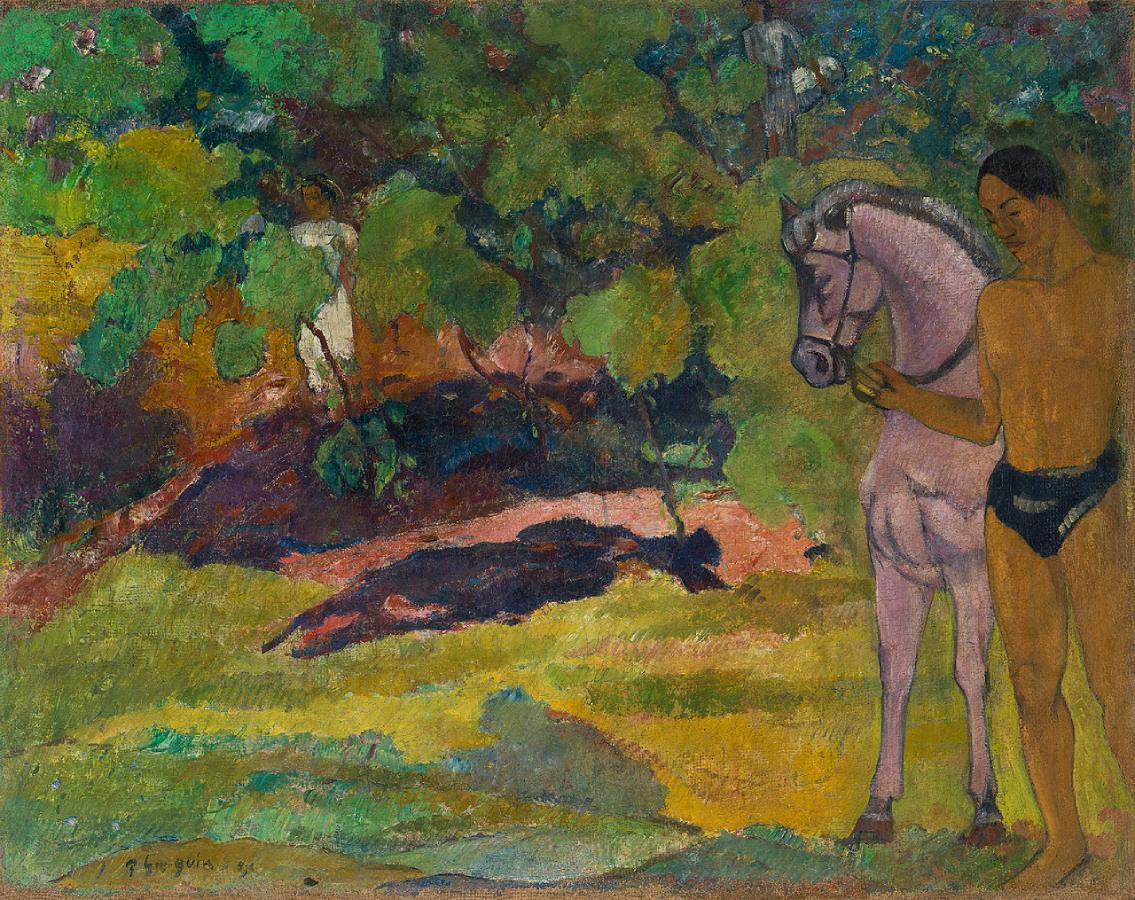

Gauguin, Paul (1848-1903)

Dans la vanillère, homme et cheval (In the Vanilla Grove, Man and Horse)

1891

Oil on jute canvas, 73 x 92 cm

Guggenheim Museum, New York

Prior to his first voyage to Tahiti in 1891, Paul Gauguin claimed—from a stance that was colonialist, paternalistic, and sexist—that he was fleeing France in order “to immerse myself in virgin nature, see no one but savages, live their life, with no other thoughts in mind but to render the way a child would . . . and to do this with nothing but the primitive means of art, the only means that are good and true.” Gauguin’s desire to reject Western culture and reside in an Indigenous society for the sake of aesthetic and spiritual inspiration reflects the complex and problematic nature of European “primitivism.” A concept that emerged at the end of the 19th century, “primitivism” was motivated by a romanticized desire to discover an unsullied paradise hidden within the supposedly “uncivilized” world, as well as by a fascination with what was incorrectly perceived as the raw, unmediated sensuality of cultural artifacts. This voyeuristic engagement with non-European cultures by artists, writers, and philosophers corresponded to French imperialistic practices—Tahiti, for example, was annexed as a colony in 1880.

The artist’s Tahitian landscapes In the Vanilla Grove, Man and Horse and Haere Mai reveal the contradictions between myth and reality that are inherent to “primitivism.” Both canvases probably depict the area surrounding Mataiea, the small village in which Gauguin settled during the fall of 1891. As richly hued tapestries of flattened forms, they are, however, only evocations of the lush Tahitian terrain, reflecting the compositional simplicity sought by the artist during his first visit to the island. Gauguin derived the pose of the man and horse in In the Vanilla Grove not from a scene he found in Tahiti but from a frieze on the quintessential monument of Western culture, the Parthenon. Gauguin painted the phrase “Haere Mai,” which means “Come here!” in Tahitian, onto the other canvas in the lower-right corner, but it does not appear to coincide with the content of the painting. The artist, who spoke little of the native language at that time, often combined disparate Tahitian phrases with images in an effort to evoke the foreign and the mystical. Evidently, this practice was designed to make the paintings more enticing to the Parisian public, who craved intimations of the distant and the “exotic.” (Guggenheim)