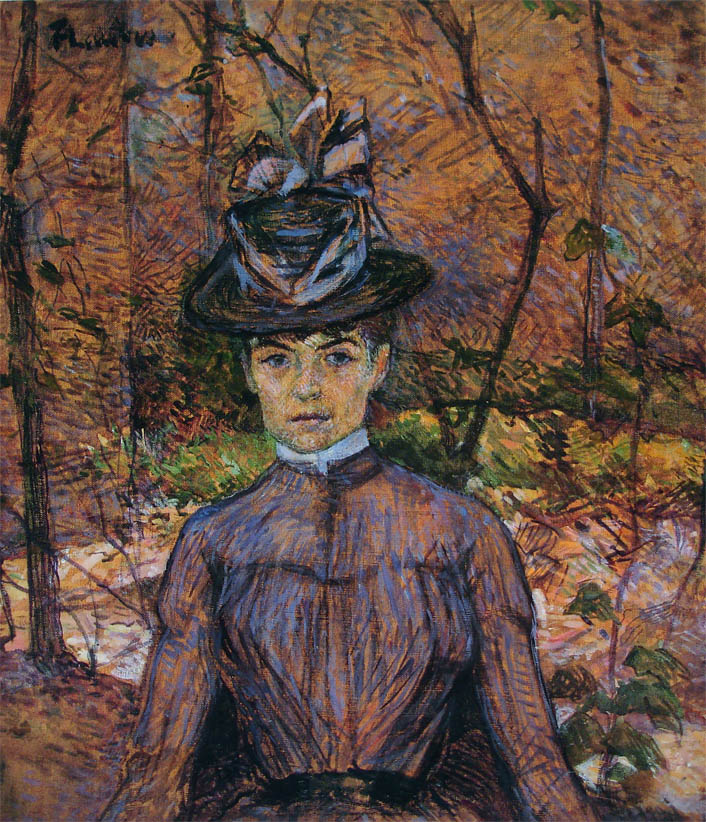

Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri de (1864-1901)

Portrait de Suzanne Valadon (Portrait of Suzanne Valadon)

1885

Oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm

Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

In 1885, at the age of just twenty-one, in search of independence and eager to escape his father’s strict control, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec left the south of France for Paris. He settled in the Montmartre district with his friend René Grenier. His integration into the life of the butte was not easy; his friends helped him to integrate, including François Gauzi, a fellow student at Ferdinand Cormon‘s studio.

In close contact with Van Gogh, Vallotton and Bonnard, Lautrec was fully involved in the Parisian artistic climate, which at that time was seeking in many ways to overcome Impressionism, and directed his research towards a painting that adhered to reality and, through formal stylization, would establish psychologically characteristic types. A disenchanted participant in the Montmartre environment – cafés-concerts, brothels, dance halls, theatres – in his paintings and in the numerous sketches taken from reality, Lautrec traced all the intimacy and sadness of this human underworld. Fundamental to this environment was the encounter with a woman who, before a series of models and lovers, entered his life and work. This was Marie-Clémentine Valade, better known as Suzanne Valadon, who lent her features to some of Lautrec‘s best-known “female types”. Marie-Clémentine was a young girl with no financial or cultural resources, born in 1865 to a seamstress mother and an unknown father. She ventured into circus activity as an acrobat, but a fall forced her to give up; she tried other humble jobs until she decided to offer herself as an artistic model. She began to be sought after by the best painters of the time, first of all Puvis de Chavannes, who was also her lover for a time. Renoir, Manet, Gauguin followed; she gave her beauty to all, she took something from all. Passionate about drawing, during the posing sessions the young model watched the masters at work; very soon everyone, particularly Lautrec, encouraged her to follow her passion. It was he who suggested the artistic name of Suzanne Valadon, because like the biblical Susanna, Marie was surrounded by “greedy old men”. With this portrait entitled Madame Valadon, artiste peintre, Lautrec confirms the role of painter that Marie had assumed.

Toulouse-Lautrec often spent time in the open-air studio. His open-air paintings were a stage in which he adapted stylistically and thematically certain values acquired from painting en plein air, not so much in the line of the Impressionists’ studies of light but in a search for greater freedom. In this painting, Suzanne is seated, represented frontally, in front of an autumn landscape. This is most likely the garden of the Vieux Forest, an area dedicated to archery, located on the corner of the Boulevard de Clichy and the Rue Caulaincourt, a few steps from the artist’s studio, where Lautrec painted various female portraits (Justine Dieuhl, 1891, Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Her body is outlined by a well-marked black contour – reminiscent of the example of Degas, for whom Lautrec felt real veneration – within which, however, the volumes seem summarily filled by broad strokes of colour, whose porosity is exalted by the texture of the unprepared canvas. The model’s face is outlined against a set of chromatic planes that have lost the rigidity and rigour of the contemporary Portrait de Jeanne Wenz (1886, The Art Institute of Chicago), already testifying to the great mastery and true ductility of brushstroke acquired by the artist. The background, a harmony of yellows, beiges and browns, mixed in diluted touches, casts a sort of bluish veil over the woman’s body, softening the character’s firm expression. The female portrait is usually a compromise between elegance and realism based on direct observation. Worldly artists have as their only concern to enhance the beauty and social status of the model. An artist in vogue at the time, such as Giovanni Boldini, made his models look as similar and flattering as possible. Lautrec, on the other hand, more lucid, like Van Gogh, went straight to the point thanks to a sober and direct descriptive manner, avoiding the temptation to “embellish”. The fact that he had a family income allowed him to avoid the obligations of “nutritious” portraits – those made to live off of all month – and to follow only his imagination; in fact, portraits made by the artist on the basis of a famous commission are rare (for example, Madame de Gortzikoff). The work in Buenos Aires must be related to a portrait on a similar subject, preserved in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen (1886–1887). The model also posed for the famous painting La buveuse ou La gueule de bois (1889, Harvard Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge; the drawing, from 1887–1888, is preserved in the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi), a social scene of depravity and misery. (Barbara Musetti | MNBA)

See also:

• Valadon, Suzanne (1865-1938)