Domenico Veneziano (c.1410-1461)

La Vergine e il Bambino in trono (The Virgin and Child Enthroned)

c.1440–1444

Fresco, transferred to canvas, 241 x 120.5 cm

National Gallery, London

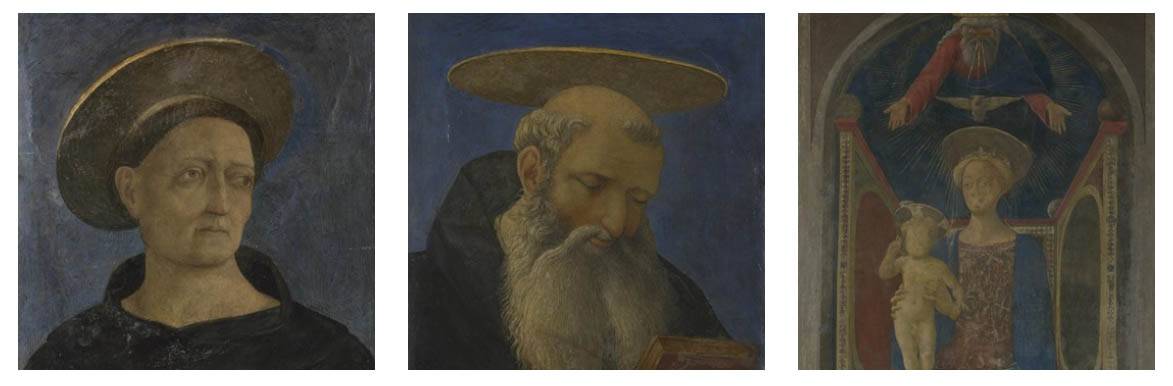

This is the central part of a fresco which was once flanked by two standing saints – one beardless and one bearded – whose heads are the only remaining fragments. Together they formed a so-called ‘street tabernacle’ in the city of Florence. Street tabernacles were like like open-air altarpieces placed on the walls of a building for all to see. Its original outdoor location explains why it is damaged in some places, for example in the faces of the Virgin and Child.

The artist has signed the image on the steps of the throne: DOMINICUS/D[E]. VENECIIS. P[INXIT] (‘Domenico from Venice painted this’). According to the sixteenth-century artist and biographer Vasari it was one of the first works that Domenico painted in Florence where he began to work in around 1430. He certainly marked his presence in the city with this work which apparently sparked the envy of his fellow artists.

We see the Virgin Mary with the three members of the Trinity – God the Father, Christ and the Holy Ghost. The painting’s grand and simple design within a painted three-dimensional arch recalls Masaccio’s Trinity, which he painted for Santa Maria Novella in Florence in the 1420s and which Domenico surely knew. Domenico also imitates the innovative positioning of the haloes that Masaccio used for the first time in the altarpiece he made for Santa Maria del Carmine. Rather than sitting upright behind the heads of the holy figures the haloes hover above, projecting in front and behind. This increases the sense of the space around them and the three-dimensionality of the scenes.

The sides of the throne also seem to jut out towards us, giving us the sense that the Virgin and Christ Child are really seated on a deep throne within this imaginary space. The throne’s arms mirrors those of God the Father; he is shown swooping in, surrounded by golden rays of heavenly light, presenting the Virgin and Child to the people on the street below. The rays coming from his mouth represent the Holy Ghost, and descend upon the dove, its symbol. Their presence confirms and emphasises the spiritual importance of the mother and child.

The image of God the Father with the Holy Ghost in the form of the dove was rare in Italian painting at this time, but it was often found in images of Christ’s baptism (such as Niccolò di Pietro Gerini’s Baptism of Christ) as they were both described as having played a role. The bold representation of God the Father shown dispatching a dove can also be found in an altarpiece by Lorenzo Veneziano, a Venetian painter, but this is shown above a scene of the Annunciation in which the Holy Ghost also played a crucial role. (NG)

These three fragments painted in fresco (painting directly onto wet plaster) come from the outside of a house in Florence. They were removed in the mid-nineteenth century. They were part of a street tabernacle, a large outdoor altarpiece, painted high on a wall. It included a pair of full-length standing saints – only the heads remain – that would have surrounded the central image of the Virgin and Child enthroned.

This painting was on a house built by a member of the Carnesecchi family, who owned several properties in the area; the street was called the Canto de’ Carnesecchi. This was a very visible spot on the route of religious processions in the city. (NG)

Carnesecchi Tabernacle:

Domenico Veneziano (c.1410-1461)

Domenico Veneziano (c.1410-1461)

Testa di santo con tonsura e barba

c.1440–1444

National Gallery, London

Domenico Veneziano (c.1410-1461)

Domenico Veneziano (c.1410-1461)

Testa di santo con tonsura senza barba

c.1440–1444

National Gallery, London