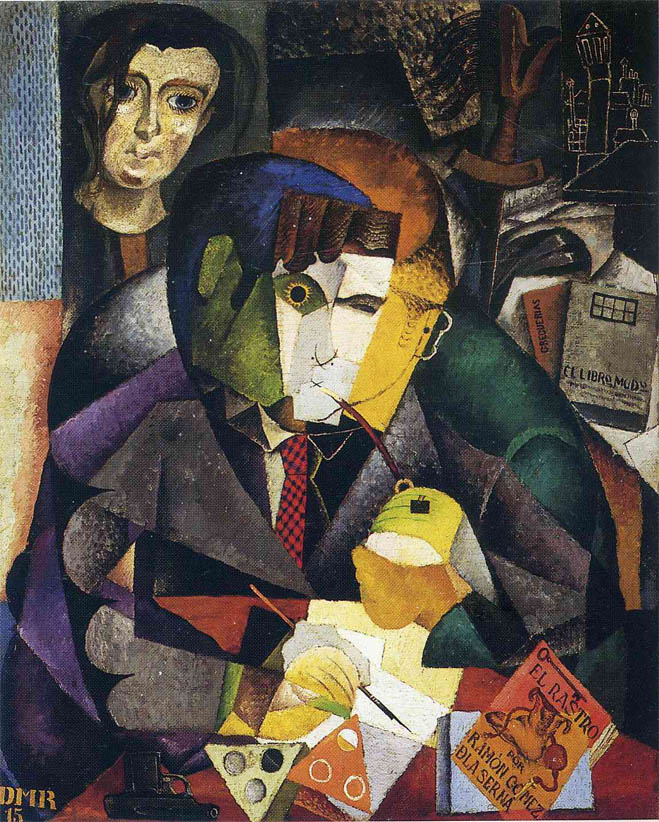

Rivera, Diego (1886-1957)

Retrato de Ramón Gómez de la Serna (Portrait of Ramón Gómez de la Serna)

1915

Oil on canvas, 110.5 x 90.5 cm

Museo de Arte Latinoamericano, Buenos Aires

See also:

• El Rastro (Madrid) | Gómez de la Serna, Ramón (1888-1963)