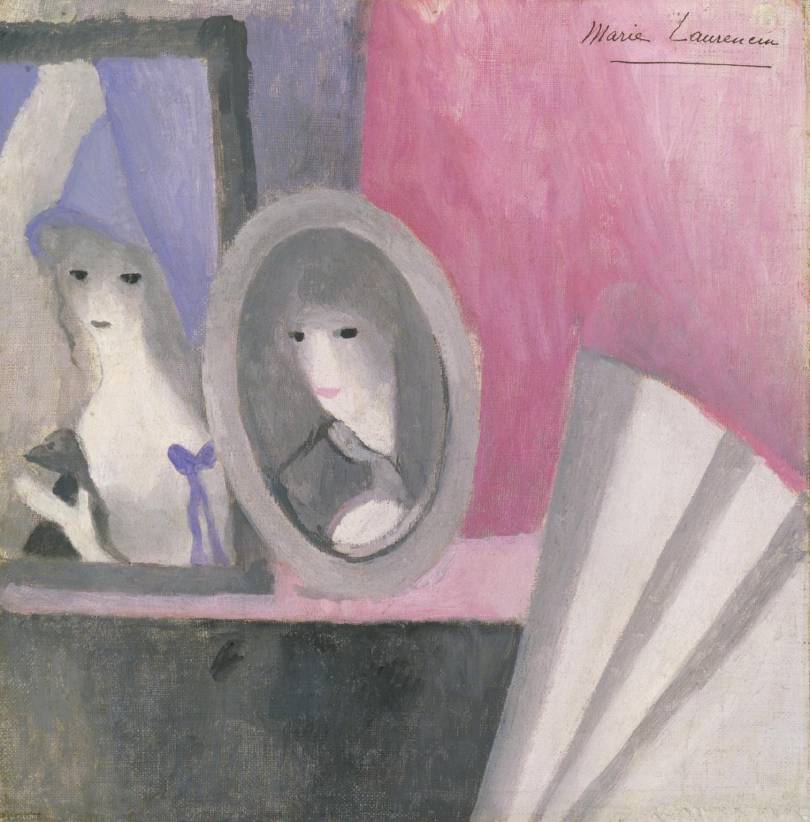

Laurencin, Marie (1883-1956)

L’éventail (The Fan)

c.1919

Oil on canvas, 30.5 × 30 cm

Tate Britain, London

The Fan is painted in Marie Laurencin’s typically restrained palette of blue, rose and grey. It depicts two women staring at the viewer from two frames on a table. It has been suggested that the woman in the oval frame is the artist herself. The identification of the other, however, is uncertain. She may simply be a model holding Laurencin’s little black dog Coco, or she may represent the idea of a loved one the artist was missing as she sojourned in Spain as an exile during the First World War. This may have been the dressmaker Nicole Groult. Laurencin had met her in 1911 and they are said to have been lovers at some point in the following years. The image is intriguingly ambiguous. The frames may represent a mirror or a picture within a picture, while the fan, which was a symbol of vanity and one of Laurencin’s favourite accessories, may indicate the presence of another person in the room.

Until the 1930s Laurencin was fêted as a member of avant-garde circles and fashionable Parisian society, and her work and artistic identity were seen as exquisitely feminine. In his 1921 critical study of the artist, Marie Laurencin et son oeuvre, the poet Roger Allard described her as ‘undoubtedly the most celebrated woman artist of today’, and wrote of her work as being coquettish and narcissistic, ‘Her art is selfish and charming and … compares everything to itself … Having no fondness except for any objects or forms of nature that resemble her … Marie Laurencin only questions nature and life in order to find more urgent and unforeseen reasons to love herself.’ (Allard, Paris 1921, pp.6-7.)

From the end of the 1930s Laurencin’s work was less highly regarded until a resurgence of interest in the 1980s. A catalogue raisonné of her engraved work published in 1981 was followed in 1983 by the inauguration of the Marie Laurencin Museum in Nagano-Ken, Japan, and by a catalogue raisonné of her paintings in 1986. Moreover, her work and sexual identity were rediscovered by feminist art historians, who propounded alternative readings of her work. Eschewing the discussions of grace and femininity of earlier theorists, some of the latest Laurencin studies underline the importance of her sexual identity within her art. She was credited by one commentator as having created ‘a visual language of female creativity and lesbian desire in early twentieth-century Paris’. (Otto 2002) In a study of a number of early Laurencin’s self-portraits, art historian Elizabeth Kahn has described her as ‘a young woman in the process of negotiating her way out of conventional femininities’, adding ‘she seemed to be searching for a unique identity that could resist the historic control of the male viewer.’ (Kahn 2003, p.xvii.) (Tate)