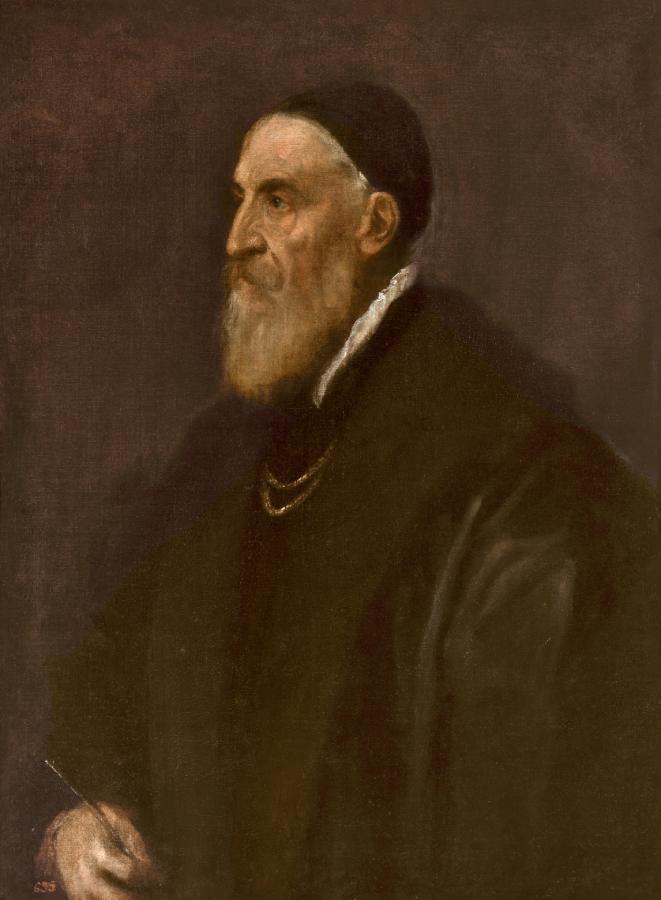

Tiziano (c.1488-1576)

Autoritratto (Self-Portrait)

c.1562

Oil on canvas, 86 x 65 cm

Museo del Prado, Madrid

Titian painted his first self-portrait before leaving for Rome in 1545. However, it was after his Roman stay that he showed the most interest in disseminating his image in order to fully establish his position in a context of intense rivalry with Michelangelo. In 1549 Paolo Giovio acquired a self-portrait by the artist for his Museo in Como, while in 1550 the painter had another one sent to Charles V that closely corresponds to the print of the artist produced that year by Giovanni Britto. In 1552 Philip II received another self-portrait that was lost in the fire at El Pardo in 1604, while in 1569 a circular one was recorded in Gabriele Vendramin’s inventory. Only two self-portraits by Titian have survied. The earlier one (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie), which the present author has suggested could be a ricordo, is datable to around 1546–47, while the present work in the Prado can be identified with the portrait that Vasari saw in 1566 in the painter’s studio as it corresponds to Titian’s age at that time, which was between seventy-three and seventy-five in 1562. While in the mid-16th century the profile portrait was an unusual format (Titian only used it for deceased sitters: François I and Sixtus VI), the self-portrait in profile was exceptional, partly for the difficulty involved in its execution as it required various mirrors or a model. With regard to the latter, in Studi Tizianeschi I, 2003, Rearick published a drawing of a portrait by Titian attributed to Giuseppe Porta dated around 1562 whose similarity to the Prado image suggests it may have provided the model. The choice of this format was thus not a random one and responded to the association of this typology with the concept of fame derived from Roman coins. Titian was familiar with this association as he had been depicted in this manner by Leone Leoni in 1537 and by Pastorino de Pastorini around 1546. It seems likely that the artist, who was by this date extremely old, would wish to set down his appearance for posterity in this manner, ignoring the individual viewer for the sake of a universal one. This idea is not incompatible with the fact that the painting could have been made for his own family, as the fact that Titian still owned it four years later suggests. As in the Berlin self-portrait, here Titian also emphasises his nobility through the inclusion of the golden chain that identifies him as a Knight of the Golden Spur, and his black clothing (the colour recommended for knights by Baldassare Castiglione in The Courtier, book II, 27, of 1527), but the fact that he is holding a brush suggests that he also wished to indicate that he owed his social elevation to his skills as a painter. As such, the present painting gives visual form to the motto that appears on Leoni’s medal: PICTOR ET EQUES, a concept also expressed by Vasari in relation to his visit to the painter in 1566. Titian’s image of himself projected in his self-portraits was carefully considered. As Jaffé noted, by representing himself with a long beard, no fringe and wearing a cap, the artist was associating himself with images of contemporary intellectuals derived from an iconographical model of Aristotle that was notably popular in Italy from the end of the 15th century. As Leoni’s medal proves, Titian had used this type of presentation from at least 1537, probably as a consequence of his proximity to intellectual circles from the preceding decade onwards (Text drawn from Falomir, M.: El retrato del Renacimiento, Museo Nacional del Prado, 2008, p. 492).