Bernini, Gian Lorenzo (1598-1680)

Il Ratto di Proserpina (The Rape of Proserpina)

1621–1622

Marble, 255 cm

Galleria Borghese, Roma

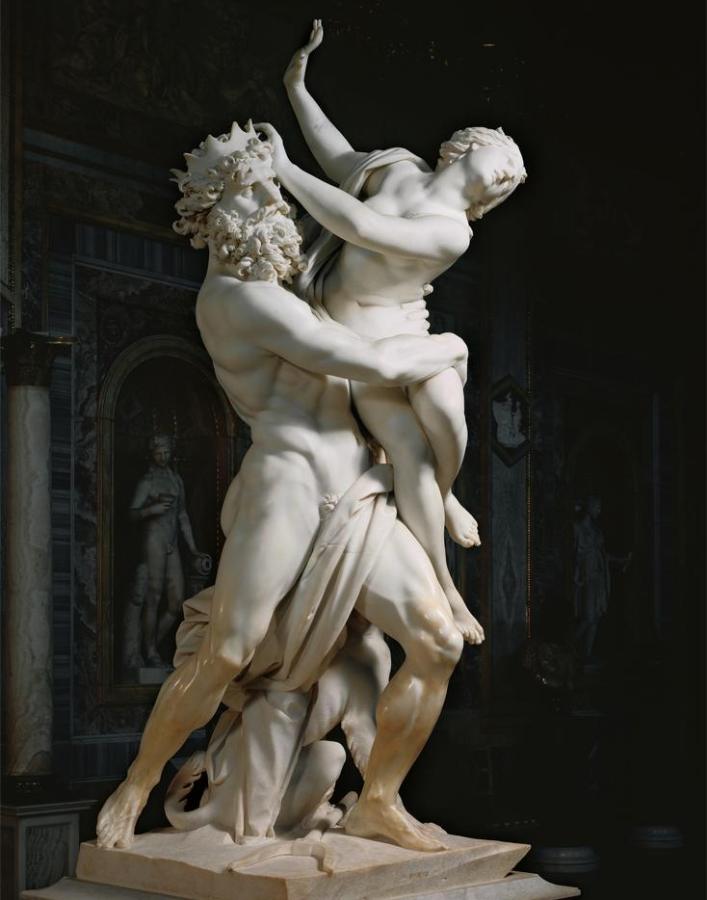

The work portrays the abduction of Proserpine by Pluto, god of the underworld. Narrated by both Claudian and Ovid, the myth tells of the abduction of the maiden on the shores of Lake Pergusa, near Enna. Crazed by sorrow, her mother, the harvest goddess Ceres, caused a drought that forced Jupiter to intercede with Pluto to allow Proserpina to return to her for six months a year. Bernini represents the culminating moment of the action. The proud, insensitive god is dragging Proserpine into Hades, his muscles so taut in the effort to hold the writhing body that his hands sink into her flesh.

The arrangement of the sculpture is pushed to the limits of the stability of the two figures, who look away from each other while remaining in frontal positions with respect to the observer. The twisting of the maiden’s body recalls the virtuosity of Mannerist taste; yet the power of the plastic form, the tension of the muscles, the sensual tenderness of the flesh and the intensity of feeling all express a new expressive idiom, founded on a naturalism which is evident in the extraordinary material execution of the surfaces. Through constant study of classical statuary and the rediscovery of ancient techniques, Bernini translated the poetry of the mythological tale into marble, measuring up to the potentiality of painting itself.

The commission for this imposing sculpture group is documented in an instalment paid to Bernini by Cardinal Scipione Borghese in 1621. A transaction for 300 scudi is recorded in the month of June of that year, which was in fact partial payment for ‘a statue of Pluto who abducts Proserpina and the head and bust of Pope Paul V sculpted in marble, for our own use, in happy memory’.

We know that the work was completed just over a year later, given that in September 1622 the white marble pedestal made to support it was ready. The pedestal has gone lost, but our sources say that it was adorned with a couplet by Maffeo Barberini: Quisquis humi pronus flores legis, inspice saevi / me Ditis ad Domum rapi (‘O you who bend down to the ground to gather flowers, look how I am abducted to the kingdom of the cruel Dis Pater’). The same stonecutter, the marble engraver Agostino Radi of Cortona, was chosen to carve the base for the Apollo and Daphne, the other great sculpture group created by Bernini for Scipione Borghese several years later. Above all, the Cardinal decided to have other verses written by Barberini engraved on the pedestal of the latter work.

The rapid succession of payments indicates that in the same month – September 1622 – the group was removed from Bernini’s studio in the area of Santa Maria Maggiore, arriving at Villa Ludovisi by the following month. A complex wooden structure was especially made to transfer the work to its destination: this was designed by the trusted architect Giovanni Battista Soria, who also oversaw the transport operation.

The exact price paid to Bernini for the Rape of Proserpine is still not clear. The final payment for the work was not made until 1624, and the sum involved also included remuneration for the Aeneas and Anchises and the David. Neither are we certain as to when the work was begun, as it has not been possible to establish the precise moment of the purchase of the block of marble.

The unfavourable political context brought about by the election of Alessandro Ludovisi to the papal throne as Gregory XV on 9 February 1621 probably explains Scipione’s expeditious decision to donate the great masterpiece to Ludovico Ludovisi, the new cardinal-nephew and an enthusiastic collector himself.

Most 17th– and 18th-century sources agree in including the Rape of Proserpine in the set of works executed by Bernini for Villa Borghese. Baldinucci referred to it as such in 1682 (the ‘beautiful group of the Rape of Proserpine, which not long ago the same Bernini had sculpted for him [Cardinal Borghese]’), while Maffei (1704) wrote that the work was begun before the pope’s death: ‘This famous group was sculpted by Cavalier Gio. Lorenzo Bernino in his youth for Cardinal Borghese while Paul V was still alive; but when Gregorio XV ascended to the papal chair the Cardinal wished to make a noble present to Cardinal Ludovisi and chose this sculpture, the most precious of the magnificent possessions that embellished his palace’. Domenico Bernini’s biography (1713) further corroborates this intention; he goes so far as to include the work among his father’s sculptures present in Villa Borghese, although at the time it was in fact held at Villa Ludovisi, which was also located near Porta Pinciana.

In representing the traditional iconography of the mythological tale narrated by Claudian (De raptu Proserpine) and Ovid (Metamorphoses, V, 385-424), Bernini draws on elements of Mannerist virtuosity while at the same time moving quickly beyond these, thanks to the expertise which he achieved through his constant study of classical statues and rediscovery of ancient techniques. While 16th-century sculpture provided models for the group’s complex arrangement and Proserpine’s violent twisting posture, the plastic power of Pluto’s muscles as he resists the girl’s torsion, the softness of the flesh and the sentiment of intense pain were unprecedented in contemporary statuary. Bernini’s new expressive idiom looked to the art of antiquity, of which Cardinal Scipione’s own collection contained extraordinary models, such as the famous Gladiator, which is in fact alluded to in the powerful, dynamic posture of Pluto’s legs. Yet Bernini also drew inspiration from important contemporary models, such as the decoration of the Gallery vault of Palazzo Farnese, completed by Annibale Carracci in 1601: the marked naturalism of these frescoes blends the suggestiveness of classical art with careful study of Raphael’s works.

The design and absolute technical mastery with which Bernini challenged the marble’s physical limits led to the emergence of a new expressive language, by means of which the myth seems entirely plausible to us. The imitation of nature is achieved through the extraordinary material rendering of the different surfaces in a direct comparison with the potentialities of painting itself.

When Villa Ludovisi was demolished as part of an urban renewal project in the late 19th century, the Rape of Proserpine was transferred to the new palazzo built for Boncompagni Ludovisi, which was later the residence of Queen Margherita. In 1908, the work was purchased by the Italian state and brought to Galleria Borghese, where it was placed in the centre of the Room of the Emperors. The original pedestal was replaced by another one executed by the sculptor Pietro Fortunati in 1911. Sonja Felici (GB)

See also:

• Ovid (43 BC-17/18 AD): The Metamorphoses (English)